Mental health medication managementWhat do we mean by mental health medication management?

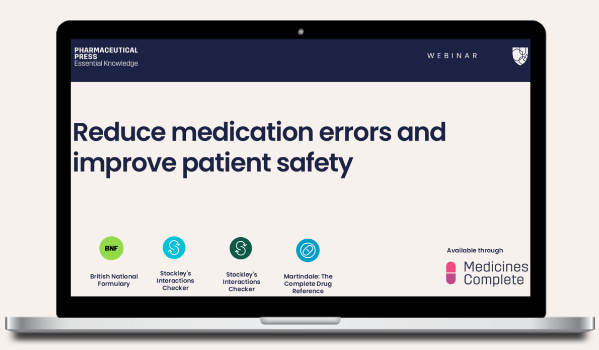

Medicines are an important tool in the treatment of mental health disorders. Around one in six adults are in receipt of mental health treatment (involving psychotropic medication, psychological therapy, or both) according to NHS England.¹

The same report found that medication is used more commonly than psychological therapies and that the proportion of patients using medicines almost doubled over the past 15 years, from around 20% in 2007 to 38% in 2022/24.¹

Antidepressant use, in particular, has risen sharply; between 1998 and 2018 the number of prescriptions issued tripled.¹

In England in 2024/25, 92.6 million antidepressant items were prescribed to an estimated 8.89 million patients.²

Antidepressant drugs was also the section of British National Formulary (BNF) with the largest number of NHS prescriptions (up by around 44% since 2023/24) and also the largest number of patients treated, with an increase of 1.61% over this one-year period.¹

The use of anxiety medications and antipsychotic drugs is also increasing.²

Please complete the form at the bottom of this article to request a complimentary trial of MedicinesComplete.

As these medicines are so widely prescribed, health professionals need to ensure that patients get the best from taking them. The broad term ‘mental health medication management’ may be used to encompass all the steps taken to do this, ranging from shared decision making about initiating a medicine, to dose titration, managing side effects, improving adherence, and to tapering the dose of a medicine gradually when it is reasonable to stop.

It’s more important than ever that health professionals are adept at managing commonly used mental health medicines and understand when to seek specialist advice.

Download our Psychotropic Drug Directory user guide. Psychotropic Drug Directory (PDD) is a valuable resource to support health professionals with mental health medication management. Available through Medicines Complete, it is a source of rapidly accessible information, advice and guidance on psychiatric drugs. Its aim is to help encourage the optimal and rational use of medicines in order to improve the quality of life for people with mental health needs.

Non-drug management

Non-drug strategies may be helpful for patients who do not wish to take mental health medication, or can be used alongside drug therapy.

Social prescribing is an approach that connects people to activities and groups in their community. People can get involved in a range of activities such as arts, gardening, cookery, and a variety of sports. This can address social and emotional needs that affect health and wellbeing. This may be helpful as an initial strategy for patients who do not wish to take mental health medication.

Talking Therapies are psychological interventions mainly for anxiety and depression.³ ⁴ They can be very effective and may also be used in a range of common mental health problems including obsessive-compulsive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, and phobias.

Patients may be open to exploring the impact of lifestyle interventions such as exercise, sleep, and changes in diet on their symptoms.

Types of mental health medication

A wide range of medicines is available to treat mental health conditions. The choice of therapy will depend on the specific diagnosis and symptoms, patient preferences, and should follow evidence-based guidance.

The medicines used commonly are summarised briefly below.

Antidepressants

Antidepressants such as tricyclic antidepressants and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are used to improve mood and quality of life, and to reduce the risk of relapse or recurrence in depression.⁵

They are also used for other conditions including anxiety and obsessive compulsive disorder. Although antidepressants are widely prescribed, there can be a stigma attached to their use and some patients may be unwilling to take them. On the other hand, some patients may request an antidepressant. There should be a discussion of the risks and benefits with all patients. Patients should be aware that antidepressants take up to four weeks to start working, the dose often needs to be adjusted and a few medicines may need to be tried to find one that works well for an individual patient. Response to treatment also needs to be monitored regularly.

Antipsychotics

Also known as neuroleptics, antipsychotics are often used to treat symptoms of severe mental illness such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and psychotic depression.⁶ These medicines can reduce acute symptoms and help the patient to function better. Antipsychotics are effective in reducing symptoms but patients frequently experience adverse effects, including weight gain, that may affect adherence. Monitoring the patient for adverse effects is especially important.

Anti-anxiety medication

Antidepressants can help manage key symptoms of anxiety, such as feeling tense, sweating, trouble concentrating, and panic attacks. Beta blockers may also be prescribed for symptom relief. Benzodiazepines provide short-term relief from anxiety but due to the significant risks of dependence or abuse health professionals are cautious about their use.⁷ Patient education and regular reviews are essential. Long-term use of benzodiazepines should be avoided.

Sleep medicines (or hypnotics)

Insomnia is a common problem, although estimates of prevalence vary widely from 5–50% depending on the definition used.⁸

Patient education on improving sleep hygiene is the recommended approach. Over-the-counter remedies, for example, containing herbal products or antihistamines, may be used short-term. A short course (3-7 days) of a non-benzodiazepine hypnotic medication, for example zopiclone or zolpidem, may be appropriate in some circumstances. Routine prescribing of hypnotics is undesirable, due to the risks of tolerance, rebound insomnia, and withdrawal syndrome.⁷ ⁹ They should be avoided in the elderly due to the risk of confusion and falls.

Mood stabilisers

Also known as antimanic drugs, drugs such as lithium are recommended to support patients with ‘rapid cycling’ (this is defined as four or more episodes of mania, hypomania, or depression a year).¹⁰ ¹¹

Lithium is a mood stabiliser and can be used for both acute episodes and long-term management, where it can reduce the risk of suicidal behaviour. Antipsychotic drugs can also be used in the treatment of mania or hypomania.

Stimulants

Primarily prescribed for people with an attention deficit hyperactivity (ADHD) diagnosis, stimulants such as amphetamines have a stabilising effect on functional impairment.¹² ¹³

Diagnosis and drug treatment should be initiated by a specialist in ADHD. Gradual dose titration is essential and can be challenging. The non-stimulant atomoxetine can be considered for patients who are intolerant, or do not respond, to stimulant drugs.¹³

Initiating mental health medication

Consent in mental health prescribing

In mental health, as in all aspects of healthcare, treatment is given on the basis of shared decision-making. Any treatment given is based on the principle of consent, or ‘permission to treat’. Patients are supported to reach a decision about their treatment, bringing together the clinician’s expertise on treatment options, risks and benefits and what the patient knows best i.e. their preferences, personal circumstances, goals, values and beliefs.¹⁴ ¹⁵

The person must be advised about whether there are reasonable alternative treatments and what will happen if treatment does not go ahead. There are some exceptions in people with a severe mental health condition, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder or dementia, if the person lacks the capacity to consent to the treatment of their mental health (under the Mental Health Act).¹⁵

Before initiating drug treatment patients should always be counselled about what to expect from the medicine, the potential side effects and when to seek advice from a health professional. The treatment response needs to be monitored carefully with all medicines used in mental illness.

Early intervention

Some mental health diagnoses benefit from early intervention through prescribing. Early intervention in psychosis, for example, has been shown to reduce the risk of death by suicide from 15% to 1%.² ¹⁶

In other conditions, however, health professionals will prefer to exhaust non-drug options before prescribing. Insomnia is a good example, where first-line treatment for adults is currently cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia (CBT-i) and improved sleep hygiene.⁸

Monitoring treatment and medication reviews

Some medicines, such as antidepressants, antipsychotics, and ADHD treatments require dosages to be titrated or adjusted according to the individual’s response. Switching to another drug within these classes may require specific protocols or guidance to be followed.

Psychotropic Drug Directory contains detailed guidance on dose titration, equivalent doses and switching to another drug within a class.

Many mental health conditions will require lifelong treatment and the response to treatment needs to be monitored carefully. It is also important to ensure good adherence with mental health medicines if they are to work successfully and with minimal side effects. Structured medication reviews (SMRs) are designed to support patients who take long-term medication, including drugs for mental health.

Patients on drugs with a narrow therapeutic range (such as lithium) will usually be subject to therapeutic drug monitoring, an even higher level of monitoring, to prevent side effects or crises.

Adverse effects

The potential side effects of mental health medication should be discussed before treatment is begun. Side effects that can occur vary according to the class of drug. Atypical antipsychotics, for example, have been shown to increase the risk of cardiovascular side effects such as tachycardia and heart failure.

While adverse events can’t be prevented completely, vigilant monitoring can mitigate the risks. Regular medication reviews give the patient an opportunity to provide feedback and learn more about their medication.

Tapering

When using medicines that can cause dependence or withdrawal symptoms, it is important that people understand the possible risks and benefits of taking them, that they are prescribed correctly and that they are not taken for longer than they are needed.⁷

People can find it difficult to stop taking their medicine, but health professionals can help them to safely reduce their dose until the medicine is no longer needed. Stopping mental health medication such as antidepressants can be challenging; the process is sometimes difficult and may take several months or more.

A step-wise dose reduction or tapering process is essential for minimising the risk of withdrawal symptoms, as well as assessing any recurrence of the original mental health symptoms. For certain drugs – such as valproate, lithium, and benzodiazepines – withdrawal is risky and it is essential that patients are made aware of this at initiation.¹⁷

Psychotropic Drug Directory contains detailed guidance on withdrawal symptoms and how to discontinue antidepressants and antipsychotics.

Robust medication management by health professionals who work with people with mental health diagnoses is part of a strong professional-patient relationship, and together with clear communication between both parties, can help ensure effective treatment outcomes and mitigate the risk of harm to the patient.

Trial form

Please complete the form below to request a complimentary trial to knowledge products through MedicinesComplete.

References

1. NHS England. Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey: Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing, England, 2023/4. [https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/adult-psychiatric-morbidity-survey/survey-of-mental-health-and-wellbeing-england-2023-24/mental-health-treatment-and-service-use] Last accessed 2 September 2025.

2. NHS Business Authority. Medicines used in mental health – England – 2015/16 to 2024/25. [https://www.nhsbsa.nhs.uk/statistical-collections/medicines-used-mental-health-england/medicines-used-mental-health-england-201516-202425] Last accessed 2 September 2025.

3. NHS Talking Therapies, for anxiety and depression. [https://www.england.nhs.uk/mental-health/adults/nhs-talking-therapies/] Last accessed 29 September 2025.

4. Royal College of Psychiatrists. CBT. [https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/mental-health/treatments-and-wellbeing/cognitive-behavioural-therapy-(cbt)] Last accessed 2 September 2025.

5. NICE CKS. April 2025. [https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/depression/] Last accessed 29 September 2025.

6. Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: prevention and management, NICE guideline (CG178). March 2014. [https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg178] Last accessed 2 September 2025.

7. Medicines associated with dependence or withdrawal symptoms: safe prescribing and withdrawal management for adults. NICE guideline NG215, April 2022. Last accessed 29 September 2025.

8. NICE CKS. May 2025. [https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/insomnia/] Last accessed 2 September 2025.

9. BNF Hypnotics. Last accessed 29 September 2025.

10. Carvalho, A. F., Dimellis, D., Gonda, X., Vieta, E., Mclntyre, R. S., & Fountoulakis, K. N. (2014). Rapid cycling in bipolar disorder: a systematic review. The Journal of clinical psychiatry, 75(6), e578–e586. [https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.13r08905] Last accessed 2 September 2025.

11. NICE CKS. [https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/bipolar-disorder/prescribing-information/lithium/] Last accessed 2 September 2025.

12. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder | Health topics A to Z | CKS | NICE. February 2025. [https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/attention-deficit-hyperactivity-disorder/] Last accessed 29 September 2025.

13. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder treatment summary. [https://bnf.nice.org.uk/treatment-summaries/attention-deficit-hyperactivity-disorder/] Last accessed 2 September 2025.

14. About shared decision making | NICE. [https://www.nice.org.uk/what-nice-does/our-guidance/about-nice-guidelines/about-shared-decision-making] Last accessed 2 September 2025.

15. What is consent to treatment for mental health? [https://www.mind.org.uk/information-support/legal-rights/consent-to-treatment/about-consent/] Last accessed 29 September 2025.

16. Knapp, M. et al (2014). Investing in Recovery. [https://www.rethink.org/media/2622/investing-in-recovery-may-2014.pdf] Last accessed 2 September 2025.

17. Planning for withdrawal. [https://www.mind.org.uk/information-support/drugs-and-treatments/medication-coming-off/planning-for-withdrawal/] Last accessed 2 September 2025.